by Helen De Cruz

The First Evening (Tune: Robert De Visée – Tombeau pour les Mesdemoiselles De Visée, dedicated to the composer’s two daughters who both died of pneumonia)

Even while her world was ending, the Marquise of E. desired to hear music.

Filters had already ceased to purify the air she breathed. The power systems that cleaned the water she drank and that sustained the gravitational field that grounded her feet were now also faltering, one by one.

On those final evenings, three musicians had gathered to play a farewell to the world that would be no more. Scattered throughout the Formal Gardens, the one hundred or so remaining citizens of Erignac sat on blankets and folding chairs, as they listened in quiet rapture to the skillful weaving together of theorbo, viola da gamba, and violin.

The Marquise looked up at the wrought iron and glass dome that spanned the entirety of her world, laced with vines, creepers, and delicate pink orchids that pointed their calyxes toward the expanse of the galaxy that could be seen beyond the glass. Who could guess this beautiful glasshouse world was dying?

The Marquise’s philosopher-in-residence, Alain de Sermisy, entered the Formal Gardens. He strolled up to her and said, “Madame, what a wonderful idea these concerts are! The people look so serene.”

That evening, the people had indeed lapsed into a kind of tranquil acceptance, their panic and frenzy of the past few months seemingly forgotten.

“Concerts at the end of the world are not my original idea,” the Marquise answered, “I got it from the report of a sinking ship on her maiden voyage in the Ancient World … The music consoles the listeners, reconciles them to their fate.”

Alain surveyed the audience. “I wonder, are you like a sea captain, wanting to go down with her ship? You could have left. You had the resources. Why did you stay?”

“I know,” the Marquise sighed. “Don’t make me second-guess myself.”

“I am not criticizing you, dear Marquise,” Alain said, “I admire how you gave up your final chance at a seat and gave it to that Elder — how were you able to surmount the instinct for survival that unites all creatures in the universe?”

“Ah well, as for the Darwinian instinct … at least Aurélie could leave; she is in good hands with her father,” the Marquise began.

Before her eyes flashed that scene of the girl in the blue satin dress, clutching her doll, as she boarded the ship and turned around. “When will I see you again, Maman?” Aurélie had asked her. The Marquise had lied, “soon, chérie. We will be reunited soon.”

“Let us talk no more of this,” the Marquise said, “why not take a walk in the grounds, and talk about Astronomy and Philosophy? I see no reason to change our custom now.”

They left the Formal Gardens and entered that part of the grounds that was called the Wilderness. It was not wild — nothing on Erignac inside the dome was truly wild — but the plants were placed with studied nonchalance to give the impression of untamed nature.

The delicious artificial breeze that blew that evening felt the way she had imagined Erignac before its decommissioning: safe, familiar, comfortable. What a contrast with what Erignac had become: dangerous, alien, sick. Erignac’s dome was a fragile soap bubble with a tenuous atmospheric balance and aging solar panels, set on a toxic moon. The bubble was about to burst.

“Look out over the galaxy,” Alain pointed beyond the iron honeycomb structure of the dome, at the vast array of stars. “So many worlds to discover! Multiplicities of living forms from the Ancient World and beyond.”

“The vastness of those infinite spaces terrifies me. I am glad I don’t have to see them by day,” the Marquise said with a shudder. During daytime, blinds fixed on the dome emulated the Ancient World’s small yellow sun and blue sky.

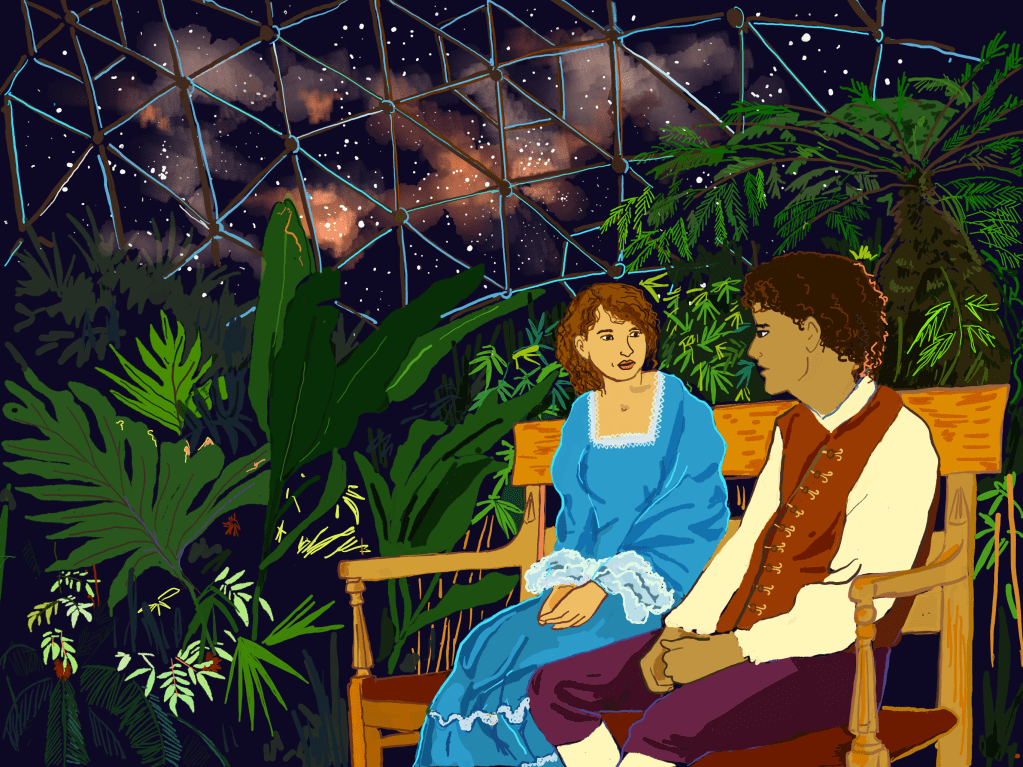

They ventured deeper into the Wilderness, along the narrow gravel path, small mangrove trees at either side, and took a seat on one of the benches in the center, enclosed by large bushes of bamboo. Alain looked quite tired — it was regrettable, the Marquise thought, that a man who had not yet reached middle age should suffer from such severe rheumatism. Ever since they had run out of steroids, he could not walk for very long.

Alain leaned back, and gazed up again at the sky, “As for me, the sight of stars at night puts me at ease. It makes me feel freer, part of a bigger world, of a connected whole. There is much goodness in those worlds beyond, and a dazzling array of forms, most wondrous and beautiful.”

“I sent out a distress signal to those dazzling worlds of yours, but it was all to no avail. No-one has come to our rescue, and now the lights on Erignac are fading.”

The Marquise noticed that the faraway music had stopped, and she hurried back to the Formal Gardens to pay the trio, though the money would be of no use to them. There was comfort in the familiar transaction of service and payment.

The Second Evening (Tune: François Couperin, Les Baricades Mystérieuses, a piece consisting of a range of arpeggios, expressing a variety of moods.)

Long tables stood decked with clean, white starched tablecloth. The Marquise of E. had taken out the silver cups, and filled the serving dishes with copious amounts of lychees, cut dragon fruit, and diced mango. She had chosen the best remaining wines from her cellar. The alcohol was a fine distraction from the fact that their drinking water had all but run out. Everyone present was thirsty from weeks of rationing to stretch their supplies. The effects of serving this wine were predictable. Maybe she could make the people of Erignac happy for a little while, or, if not happy, at least help them forget.

How the Marquis of E. would have complained about this, had he still been around! Not about making people drunk, or wasting expensive vins de table — no, about the fact that his wife was serving them! He had often told her, “Always be the one to be served, you should never serve anyone, not even a cup of coffee, lest people get any ideas.”

The Marquis of E. had already left two years ago. He took off on one of the few near-lightspeed ships as soon as he heard that the Alliance of Outer Worlds would withdraw its technical support (as it was euphemistically put) from their little moon. Erignac had become unsustainable. They weren’t worth the expense.

The Marquise of E. poured Alain’s silver glass about halfway full with red wine — an exquisite and rich Pommard from a very fine year on some distant planet. Alain took a sip, then gingerly picked up a few lychees and pieces of mango with the tongs and placed them on a little dish.

“Madame, the fruits of the Ancient World are the most delicious I have tasted!” he said, taking a piece of dripping ripe mango from the dish and eating it inelegantly. “I will miss that, among many things.”

“How is it that you have never before eaten mango, or even durian before your arrival here?” the Marquise remarked, “You can find them on so many planets and moons.”

“Durian! Tasting that for the first time was quite the experience. Transformative. The taste is a marvel!” Alain said, smiling.

The Marquise drank and considered, not for the first time, on what remote world Alain de Sermisy had lived before his arrival on Erignac about eighteen months ago. She had often wondered about it, but on this topic, Alain was an impenetrable fortress.

“I wonder,” Alain went on, “do you know what fruits grow beyond the dome? Did people ever try to eat them?”

The Marquise finished her glass, and did not refill it. She wanted to keep her head clear. “No idea. There are plants that look like trees, insect-like creatures too, so it’s possible. But no human has survived long enough beyond the dome for us to find out more. It is too late now.”

“Surely, you must have tried?” Alain asked. He peeled a lychee slowly, almost mindfully, contemplating for some time the semi-translucent white orb of fleshy fruit before popping it in his mouth.

“We did,” the Marquise said. “When Erignac was first settled people were curious about the dense vegetation. But our enthusiasm faded when we realized that leaving the dome was impossible.”

“What do you mean with ‘impossible’?” he asked.

“Well, whoever ventured out, even in the most protective space suit returned in a state of delirium. And then, within days, they died of a mysterious ailment no doctor could cure. That dampened any adventurer’s zest.”

“So, you have few first-hand reports about what it’s like outside the dome?” the Philosopher insisted.

“Only incoherent ramblings about how lovely and beautiful it’s out there, by people who died shortly after. No, you must give up these notions, the world beyond the dome is uninhabitable,” she said.

Why did he bring this up now? It was too late — the glasshouse world within the dome of Erignac was dying, and they were trapped inside.

The Third Evening (Tune: Marin Marais, Les voix humaines, a piece for the viola da gamba that alludes in its phrasings to the subtlety and diversity of human voices.)

That evening, the musicians played as if nothing else mattered in the world. They almost floated as bows and fingers darted across strings. The gravitational field had weakened and it looked like everyone who walked was dancing a Sarabande, with high, slow steps followed by leaps. It would have been fun were it not for the low levels of oxygen.

The ensemble played Marin Marais’ Human Voices. The Marquise of E. could not explain her love for this piece. It was not particularly complex, but something about that music called out to her from across the vastness of the galaxy, across countless generations who lived, died, and who found it worthwhile in that brief flicker of intermittent time to preserve this piece.

She sat listening with tears in her eyes. The Philosopher was listening too, a tactful distance away from her. She beckoned him closer. “Remember, Alain, when you first arrived here, and asked me to be my Philosopher-in-residence?”

“If I may say so myself, Madame, you made an excellent decision hiring me,” Alain said, sitting down on one of the folding chairs near her.

“Even now?” the Marquise of E. asked.

“Especially now,” Alain said.

“How about you?,” the Marquise inquired, “You arrived on a dying world, with not enough fuel to escape. Doesn’t that bother you? Or, being a Philosopher, are you above such trivialities as the fear of death?”

He pulled the folding chair closer to her and said, “I don’t think there are many creatures who can overcome such a deeply-rooted instinct, and in addition … There is regret in the prospect of never being able to see your friends and family again. No Philosophy in the world can insulate you against that sense of loss.”

“So, what is the point of Philosophy then?” she asked.

“Philosophy is unavoidable, because Philosophy is born in wonder. You cannot look up at the stars without marveling.”

“What I marvel at is the utter silence of those vast spaces and worlds of which you speak so fondly,” she said, now also looking through the dome’s glass at the sprawling mass of stars. “If the world is teeming with intelligent alien life, why haven’t we seen them?”

He followed her gaze and asked, “How do you know that you haven’t?”

She answered, “most scientists believe that advanced intelligent aliens would try to colonize our world, dominate us, domesticate us, perhaps even eat us. It would be foolhardy to contact them.”

“And yet,” he objected, “you did contact them. You sent out that distress signal.”

“I was out of options. We were cut off with not enough spaceships with near-lightspeed functionality to get us all to safety. Worse, the first ships left only at half-capacity.”

“Those wealthy people have no regard for others. Across the universe, it seems that wealth makes you numb to the plight of others,” Alain scoffed, then checked himself, “present company excluded, of course.”

They got up, and he leaned on her arm as they walked around the no-longer functioning fountains of the Formal Garden in that strange, low-gravity stride.

The Marquise added, “Also, I thought that Erignac would be of little use to any space aliens bent on enslavement or conquest. So, I wagered — in vain.”

“Madame, not everyone wants to own or kill everything beautiful they see,” the Philosopher remarked. As if to demonstrate his point, the viola da gamba had begun to play a slow solo, and the evening blooms released their sweetest scent.

Alain continued, “Maybe an advanced alien civilization has different morals and customs to yours. Perhaps they feel that love must be universal, that we must show love for all creatures near or far. Maybe they feel at one with the universe, and that feeling urges them to help.”

“But are these not idle speculations?” The Marquise asked, “Does Philosophy allow us to draw such far-reaching conclusions? I, for one, do not feel ‘at one’ with the universe at all. If anything, I feel cut off. I had to make the painful decision to shut down all interstellar communication systems months ago to save energy. Presently, we are a tiny raft in a vast, black ocean, alone and adrift.”

The Philosopher looked upon the Marquise with a mix of pity and urgency. “You may not be able to communicate anymore, but for all you know, somewhere, someone may be watching you, thinking about you, caring for you.”

“For all we know? Ah, that is religious naiveté which we left behind?” the Marquise said dismissively, “No, no watchful god or spirit will come and save us. The only things that matter are cost, efficiency, and profit — I know that now. When I sent that distress signal, that cost us months of energy we might have used to stretch it out here. The only one who came since I sent it out was you.”

“Yes, I came,” the Philosopher said, “I heard your call, and I came.”

“What good does that do?” the Marquise cried, “You are right that we will always need Philosophy, but I need to live! What possible use is Philosophy to me now?”

At times, the Marquise regretted sending that signal out in the starry void. However, in doing so, she also did all she could, and what else can anyone do?

The Fourth Evening (Tune: Jean-Philippe Rameau, Les Sauvages, a choral piece where two First Nation people praise their “peaceable forests”.)

The air had become more difficult to breathe the past 15 hours or so, as people of Erignac had gathered to hear the musicians for their final performance. The discomfort of lack of air had made the audience emotional, hitting home that this was the end. To make matters worse, the cooling system had also shut down. Some people let go of all restraint. They cried hot, desperate tears, for themselves, for those who left them behind, for children they would never see again.

As the tune died away, Alain de Sermisy unexpectedly stepped onto the podium. All eyes were fixed on him as the yellow evening beams of Planet 2MASS J34244 cast a spotlight on him.

“Listen, People of Erignac, heed me!” He leaned on a cane and scanned the small crowd. His voice, in spite of his apparent physical discomfort, resounded clearly. “I have been speaking to your ruler the Marquise, and we have discussed a future for you, if you want it. My people have been observing you for a while.”

He gestured at a section of the dome. “There is a space station of ours there, situated on one of the Lagrange points of the planet and Erignac. We came as soon as we heard your call.”

The Marquise of E. asked, perplexed, “Are you telling me you actually came in response to my distress call?”

“Didn’t I tell you we did? We set up the station and I arrived in a smaller craft, to talk to you, while the rest of us figured out how to help you, given the local climatic and ecological conditions.”

“How is this possible?” The Marquise gave him a long, probing look, and could not discern anything out of the ordinary. “You are human, just like us. Or are you not? Or convergent evolution…?”

He laughed. “Oh, I didn’t look anything like you. Convergent evolution to this extent would be a miracle… But I wear a skin that allows me to live under the dome. The skin is human-shaped, as the conditions under the Dome are especially fit for humans. Or they were, until now.”

“Who are you, then?” the Marquise asked.

“I am a Philosopher,” Alain said, “It is an important profession for us. We have made skins for all of you that would make it possible to live on Erignac. The world is lush and beautiful outside of the dome. The fruits appear to be delicious, and you will be able to eat them…though nothing quite compares to a fresh, juicy mango.”

A soft hum arose in the audience — the faint stirrings of hope.

“Some sort of suit…,” a woman in the small crowd mumbled.

“It is not a suit. The skin radically alters you, like becoming human has altered me. It is a new way of life. If you put it on, you cannot go back to who you were,” Alain said.

A silver-haired Elder in the audience called out, “so, if I understand you correctly, you would be giving us these skins so we can leave this blasted dome and live freely on Erignac.”

“If you want them,” Alain said. “We have fashioned enough skins for everyone here. They won’t wear out or tear.”

“But how will we pay you?” another woman (who also happened to be the theorbo player) asked.

“We don’t need payment,” he answered.

“But surely you want something,” the theorbo-player persisted.

“Your existence is gift enough for us,” Alain said, “Our people have gained so much simply by observing other beings: how they can do things right, or wrong. And our Philosophy is Universal Love — we practice care and concern for the entire universe in all its wondrous forms. Ultimately, we are all connected.”

He took one of the folding chairs, and waited in silence as the people discussed among themselves, making no further attempts to persuade them.

After a while, a sleek, black ship descended onto the remaining operational docking station.

Later that evening, most of the people of Erignac had decided to accept the gift of Alain and his mysterious people. They realized that, in order to be saved, they needed to give up their old selves. With some trepidation, the humans donned the skins, a stretchy bright green stuff that resembled moldable wetsuits. It slid onto them with surprising ease. The theorbo player tentatively plucked a few rapid arpeggios to test if her new, bright green fingers were still capable of playing music. One by one, they left the dome through a small opening made in one of its glass panels.

A few holdouts, however, wished to remain in the dying dome. They believed there was no way to trust these aliens, and the prospect of changing so radically did not agree with them.

The Marquise of E. was one of the last to depart. Only when there were no more people who would be convinced, she was ready to go. Her head was spinning from the oxygen deprivation and the almost unbearable heat, and she needed assistance with the skin. Alain held it out for her, averting his eyes so she could undress without embarrassment.

“So, are you excited?” he asked, the excitement clear in his own voice.

“More anxious than excited,” she breathed as she squeezed her legs into the tight skin. “Once I have put this on, I will change. I don’t really want to change — I still don’t. That’s why I didn’t leave Erignac in the first place. People thought I was being self-sacrificial, but in reality, I was tired of moving and had grown fond of Erignac.”

“Those past motivations do not matter,” Alain said. “This little moon is very beautiful. The animal life forms — oh, delightful! I am so excited for you that you get to explore them! There is a big and wild country out there. A true Wilderness.”

“Thank you,” said the Marquise, now able to breathe freely again. She had the sense that this was their final adieu.

“Will you accompany us?” she asked anyway, and said shyly, “I have grown rather attached to our conversations.”

“No, my people must attend to others now. But you will have no difficulties because Erignac is an easy world and life will be simple and straightforward for you. Also…” he hesitated, and added, “my body is quite worn out and exhausted from all the previous transformations. I cannot endure yet another one, so I must remain here.”

“What?” cried the Marquise, “Surely, you cannot remain to die here, in the dome? That’s not possible! I cannot allow it. As your employer, I say no.”

“Don’t be upset,” he said softly, “The universe is in constant flux. We all change all the time, death is another transformation. And I will provide comfort to your remaining subjects here in the dome while they complete theirs.”

As she had fitted herself into her new skin, the Marquise stared at Alain in amazement, now only for the first time truly seeing him through her new, more discerning, eyes.

He smiled at her encouragingly, as she stepped out of the dome, into the true Wilderness of Erignac.

Helen De Cruz is the holder of the Danforth Chair in the Humanities at Saint Louis University, Missouri. She is author and editor of several books, including Philosophy Through Science Fiction Stories (with Johan De Smedt and Eric Schwitzgebel, Bloomsbury, 2021), and Philosophy Illustrated (Oxford University Press, 2022). She also plays the Renaissance and archlute, makes digital artwork, and dabbles in writing fiction.